In Europe as elsewhere, corporate Duty of Care approaches are on the table and stand at varying degrees of implementation. Two elements of the European Union’s Green Deal indeed require companies and financial entities to step up their Human Rights and environmental due diligences. First, the EU’s Green Taxonomy, but also the Sustainable Finance Reporting Directive (SFRD).

Mapping environmental and Human Rights risks is therefore of the essence for any company or investor either based or working within the European bloc. It can all be boiled down to setting up an action plan. Then verifying and collecting feedback on the impact of implemented measures and ultimately documenting the entire process.

The Urgency of a Systemic Corporate Duty of Care

For the last 20 years, social audits have systematically highlighted the same key risks. Namely, safety, forced labor and overtime… As strategic as they might be, certain purchasing categories or geographies therefore intrinsically generate major risks.

Under the Equator Principles, companies dependent on external financing are more and more required to justify their impacts. As a result, they must take position on a growing series of complex and sensitive issues. The latter include the population resettlements, human trafficking, social unrest in key territories, the cohabitation of economic activities, down to respecting traditional or religious activities in the course of program development.

Since COP21, climate issues have become an integral part of the Human Rights agenda. Anticipating on the COP15 on biodiversity, scientific and political communities have aligned on the potent intersection of environmental conservation and Human Rights enforcement.

A 3-Step Approach to Mainstreaming Corporate Duty of Care

Apprehending these different issues is one thing, indentifying actionable convergences entirely another… To say nothing of their obvious political dimension. Local leaders may indeed seek to instrumentalize Duty of Care issues. This will ultimately advance territorial development agendas with a primarily political agenda. In the face of such complexity, investors and companies must more than ever demonstrate their ability to:

- Address a broad spectrum of issues in order to map their specific risks,

- Conduct proactive risk mitigation efforts,

- Deliver comprehensive progress reports.

Anticipating Other European Regulations

The upcoming EU due diligence directive will undoubtedly echo other regulatory levers, including the U.S. Customs embargo policy. Numerous Human Rights due diligence approaches are in fact emerging at the national and multilateral level. All signals ultimately point to the urgency of developing solid Human Rights policies. Duty of care Action plan should be a prerequisite to doing any business.

The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive notably covers Human Rights issues. From 2023, some 50,000 European companies will in fact needs to develop reliable and comparable data on these issues. Any business with more than 250 employees will indeed have to adapt to these sustainability standards, in a manner adapted to its capabilities. That is, not just multinationals.

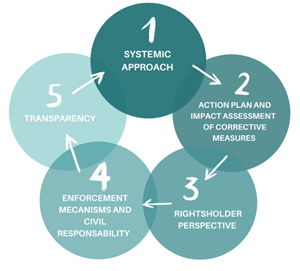

5 Core Principles for Effective Corporate Duty of Care

The question is not so much whether or when the private sector should take up due diligence… but how. But then, within what scope? With what degree of urgency? To address these very questions – and more – Ksapa ventures 5 core principles for conducting effective due diligence:

1. Adopting a Systemic View of Priority issues

The issue of Human Rights is as complex as it is sensitive. To a certain extent, it can be even more difficult to address in a private sphere than in the civil society. It is a fact companies and investors are regularly criticized for Human Rights abuses – and consequently held accountable for risk mitigation. That said, their efforts in that regard are almost automatically met with suspicion.

3 levers to Conduct Comprehensive Due Diligences

They must therefore mobilize a variety of skillsets, internal functions and experiences in the service of due diligence – and risk analyses in general. This approach also involves questioning likely organizational biases, instead adopting the most systemic Human Rights approach possible. With that in mind, here are 3 key principles to guide businesses’ and investors action:

- Considering key entities – be them assets, investments or factories – in light of the dense International Bill of Human Rights. This pushes organizations to question at least once the relevance of any given right in the scope of their own operations. From there, they will have to assess the probability of the occurrence of a risk in their concrete operational context;

- Multiplying sources, from employees to subcontractors, neighboring communities, etc. This, in an effort to analyze key realities in relations to their impact of the everyday life of various rightsholders. Special attention should therefore be paid to vulnerable segments, who will need to be identified based on a series criteria as objective as possible. These can range from statistical realities of discrimination and marginalization to income or education levels and rights awareness, etc.;

- Make each stakeholder’s roles and responsibilities as explicit as possible. An organization’s ability to address these issues will differ from one context to another. It is for instance not the same to operate from a position of majority control, as opposed being a minor player in a joint venture. It all comes down to an entity’s capacity to positively influence and mobilize local economic players.

2. Calibrate Action Plans and Corrective Measures

There can be no complete risk analysis – much less a Corporate Vigilance Plan – without meaningful stakeholder engagement. Otherwise, organizations quite simply lack the teams, resources or tools to manage the diversity of issues they are met with. To say nothing of addressing these issues across their entire value chain with the right level of granularity all the while adapting to local specificities!

Organizations have everything to gain in establishing a continuous, proactive and open dialog with priority stakeholders. Only then can they fully apprehend their risks at a local level. This is perhaps even more important in relations to ensuring the relevance of their remediation measures and, ultimately, monitor progress over time. Reality, however, requires stakeholder dialog efforts be tailored to a project’s lifecycle:

a) During Project Planification

Upon planning a project, organizations must identify its key stakeholders. This involves mapping its positive and negative impacts, both actual and potential. How else, after all, can they determine risk severity? The potential for remediation? Its own influence in mitigating these risks? From there, it will be a matter of sounding out communities aspirations and requirements as well as the resources at organizations’ disposal. This will allow them to adapt in subsequence project phases. This can for example involve embedding Human Rights risk remediation considerations in contracts and negotiations.

Companies often underestimate their ability to address Human Rights issues. This is particularly true when they are dealing with public authorities responsible for channeling foreign capital. This should however not discourage (quite the contrary) them from setting up guarantees with regards to complying with international standards, such as on the conduct of public consultations, population resettlements or the validity of property titles. These are but examples of the sensitive issues local authorities will have to decide on before investing in a territory. Once installed and this negotiation phase completed, an organization’s ability to influence local public authorities will be considerably weakened…

b) During Project Implementation

When it comes to project implementation, ongoing stakeholder dialog at a local level is particularly valuable to decision-making. It is indeed always easier to proactively address a sensitive issue than to manage the consequences once the damage has been done. It is any case (much) less costly. Wherever economic and traditional activities are expected to cohabitate – think industrial plants interacting with fishing activities or religious and sacred sites, etc. – upstream consultation often allows viable solutions to be identified.

c) During Project Monitoring and Evaluation

During the monitoring and evaluation phase, organizations must secure direct and trustworthy stakeholder dialog. Local stakeholder are directly confronted with the possible impacts of the project, whether positive or negative.

It is therefore essential to set up engagement mechanisms to give them a chance to contribute to steering the relevant corrective measures. This can involve discussion circles, contact points, social media…. For example, subcontractors who set up temporary operations near villages in violation of the rights of local residents must be sanctioned. This requires formalized contractual clauses and awareness-raising efforts on the part of all companies involved. Stakeholder dialog with local residents must be put in place to ensure their trust as they report their grievances.

That said, a project’s operational environment is constantly evolving. An agricultural development project could face rural exodus or, on the contrary, excessive land artificialization linked to rapid urbanization. Organizations must therefore have a care to update their risk mapping correspondingly. In that as well, stakeholders have a key role to play.

3. Including and Disseminating a Rightsholders’ Perspective

Engaging stakeholders as part of a Duty of Care process entails identifying just who should get onboard. Companies tend to use generic stakeholder maps which cover mostly institutional stakeholders – typically, financial partners to public authorities, etc. This often covers only half of the job. Beyond that, it is a matter of identifying the most sensitive stakeholders. This to convene a diverse set of parties, bearing in mind they are precisely the ones most difficult to reach and engage. A rural electrification project will for example have to approach people inherently disconnected from conventional grids.

Creative approaches to documenting stakeholder perspectives can thus involve the following:

- Social Media offer the richest database available to identify local players and initiatives likely to contribute valuable expertise in the scope of a due diligence or stakeholder consultation effort. However, particular care must be given to check whether using this very tool is appropriate to engage the desired stakeholders. They may indeed be quite detached from social media. Either because of their age, literacy level or as a result of the broader digital divide;

- Prioritize Vulnerable Groups. Engaging visible minorities is of the essence, as they can share practical experience. This could for instance empower a company’s to tap into concrete feedback on the impact of women’s empowerment efforts or the actual living conditions of migrant workers;

- Disintermediate Stakeholder Dialog. The more distant stakeholders are from an organization’s operations and representations, the more they call for structured dialog options. It is for instance key to conduct direct interviews with these stakeholders to validate the relevance of a organization’s working hypotheses. On the one hand, this supports a better understanding stakeholders’ daily realities through their own words; on the other, it helps continually reassessing the effectiveness of the resulting action plans.

4. Activating Enforcement Mechanisms and Access to Remedy

Ongoing stakeholder dialog processes allow key players to fully participate in reaching key decisions with regards to project direction or resource allocation. That way, they quite literally have a say in program implementation and the related capacity-building efforts (communication, transparent budget oversight, etc.). Stakeholder engagement mechanisms typically include the following:

- Social media presence and online discussions,

- Regular communications on project progress,

- Information desks,

- Multi-stakeholder community development committees/councils,

- Project advisory committees,

- Grievance mechanisms.

The development of appropriate grievance systems stands at the heart of ongoing discussions relative to the forthcoming EU mandatory Human Rights Due Diligence Directive. The reason is these tools are key for organizations to expand on strictly top-down grievance management approaches and ensure access to remedy for potential victims – whether in civil or criminal court. Transparency is therefore a prerequisite to ensure the effective governance of stakeholder engagement efforts.

5. Operating in Full Transparency

Ours is an era of constant information, met with the growing digitalization of organizations. Enforcing a Duty of Care policy and action plan demands organizations make sincere efforts to understand, share feedback and develop solutions. As a result, due diligence methodologies must necessarily be made explicit for companies or investors to explain and justify how they identified and prioritized their risks. They must then document the supporting dialog efforts and widely share relevant information with their stakeholders.

Due diligence are however no about working miracles. Organizations do not control all their risks. Even less so alone. Endemic issues in fact require collaborative work, even if it means tackling only part of the issue. However, a logic of continuous improvement will always be more socially acceptable than (perceived) corporate inaction or opacity. In other words, due diligence efforts demand companies say what they do… and do what they say. This is all the truer in the case of Human Rights, given these issues are particularly complex, sensitive and in constant evolution.

Understanding Corporate Duty of Care By Assessing its Limits

Growing constraints put the onus on investors and companies to deliver robust Duty of Care policies and plans. It all boils down to better understanding, mapping, acting and measuring risks, for key players to be in a position to unassailably prove their operations cause no harm, either in terms of Human Rights or for the environment. Anything less cannot be considered professional.

It remains key issues have remained on the sidelines – to date:

- Digital Technologies – Digitalization challenges the conventional Bill of Rights and with it, the related Human Rights risk assessment methodologies. Consider how workers typically migrate from one country to another to work on construction sites. Managing their data can generate key Human Rights risks, as it may help governments as they strive to control, at least digitally, these diasporas.

- Climate Action – and environmental issues more generally – Despite obvious links, some are reluctant to integrate Human Rights and environmental issues as part of their due diligence. Think how climate impacts in certain territories are tied to water stress management (and community welfare as an immediate result).

- Customer Relations – While the focus is rightly on subcontracting and upstream supplies, customers’ usage of products or services also raises key interrogations. The rise of Big Data seems to amplify rather than correct the resulting risks. On the other hand, by acknowledging certain profiles have historically fallen prey to discrimination, service providers could work with customers to develop relevant corrective measures.

This entails due diligence efforts move beyond conventional considerations, the likes of working conditions in subcontracting. Questioning these boundaries indeed allows the private sector to anticipate the increasing complexity of due diligence expectations. In that effort lies the key to align companies and stakeholders on effectively addressing the many risks of our turbulent times.

As a sustainability and corporate responsibility consultant, Margaux joined Ksapa with international experience in public, private and non-profit organizations. She had previously worked for the Deloitte and Quantis sustainability consultancies, lobbied for environmental research on behalf of the INRA and contributed to Total’s extra-financial reporting.

A Franco-American citizen, Margaux holds sustainability certifications from the IEMA and Centrale-Supélec on top of a Masters degree in History, Communications, Business and Internal Affairs.

She is fluent in French, English and Spanish.

-

Margaux Dillon

Président et Cofondateur. Auteur de différents ouvrages sur les questions de RSE et développement durable. Expert international reconnu, Farid Baddache travaille à l’intégration des questions de droits de l’Homme et de climat comme leviers de résilience et de compétitivité des entreprises. Restez connectés avec Farid Baddache sur Twitter @Fbaddache.

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid BaddacheSeptember 29, 2023

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache