For companies intent on engaging smallholders, designing an effective training and communications strategy is key. Selecting the right channel (or combination thereof) can achieve the desired results at an acceptable cost. Here, Ksapa outlines key tips to that affect, based on its expertise and ongoing programs.

The Business Case for Engaging Farmers via Training and Communications

Businesses can improve their quality, traceability and scale all along their supply chain by strengthening their training and communications strategy with smallholding suppliers. In traditional supply chains, off-takers (or firms) purchase crops from independent middlemen and collectors. They could indeed be twice removed from the farm gate… or more.

Although this supply chain strategy requires little investment, it generates four key issues:

1. Firms have little leverage to improve crop quality, especially when problems originate on the farm. Because they are not interacting directly with farmers, they cannot incentivize suppliers to improve farming and post-harvest techniques. Neither can they effectively resolve disputes.

2. Firms often have limited means to comply with traceability standards. That said, many in the food industry demand full traceability to ensure environmental and social sustainability standards.

3. High and low quality outputs often end up mixed together in traditional supply chains. They indeed come from thousands of different farms, often with minimal tracking. By the time crops reach middlemen and off-takers, the product often requires expensive sorting processes to meet quality standards.

4. With layers of collectors between themselves and smallholders, off-takers face major difficulties in providing inputs and technical advice to increase productivity.

Each of these problems emerges because traditional supply chains lack genuine relationships and essential training and communications strategies between off-takers and farmers.

Effective Strategies, Solutions and Best Practices To Engage Farmers

The types of relationships supply chain managers use to share and collect information affects the frequency of communication, its quality, and its reach among farmer suppliers.

These communication channels generally fall under three categories:

1. Face-to-face interactions between firm or partner staff and farmers;

2. Written materials such as manuals, brochures and product labels;

3. Information and communication technologies such as radio, Internet kiosks, tablets, computers, video and cellphones.

Combining Training and Communications Strategies for Optimal Impact Among Farmers

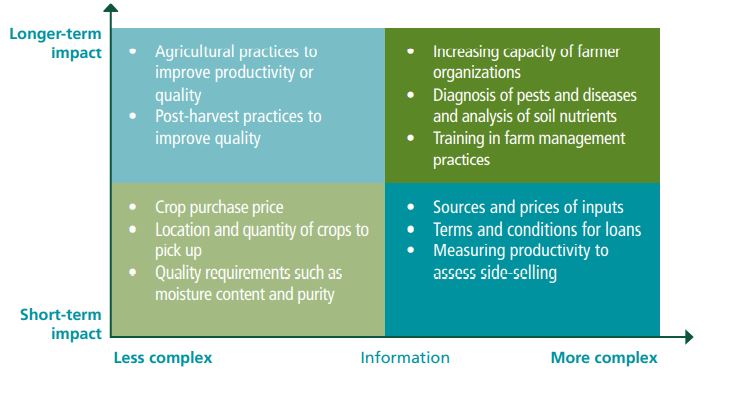

Effective training and communications strategies will likely use a combination of these mutually reinforcing channels. The frequency and difficulty of communications increases as supply chains become stronger and more developed, however.

Basic supply chains (involving one middlemen active in an aggregation capacity) may share delivery and payment information. On the other hand, more complex supply chains disseminate information on crop prices, traceability, training on improved agricultural practices, certification data, product specifications, finance opportunities and the weather. Communication along complex supply chains may also flow in both directions, from firms to farmers as well as from farmers to firms.

Field Staff: Effective but Costly, Therefore not Scalable Overall

Agricultural extension workers, also known as field officers, are often the first lever that firms think of when implementing an elaborate outreach program. It may take the form of basic technical trainings or that of a more elaborate direct sourcing strategy to secure their supply.

Accounting for the Cost of Effective Training and Communications Strategies

While face-to-face communication enables comprehensive and detailed messaging to farmers, it is also costly. According to the IFC, the cost of face-to-face training typically ranges from USD 50 to more than USD100 per farmer and per year. Various factors influence such costs (prevailing salaries and managerial overheads, for instance). That said, the cost and time of transportation appears to be the main constraint, given farmers are usually scattered.

This model is rendered more difficult to implement by the fact qualified individuals tend to prefer no to travel too soon after they come onboard. With that in mind, written materials (such as manuals) and new technologies can sometime reduce the need for extension workers. In very specific circumstances, they can replace them altogether. Cutting back on extension staff however drastically affects best practices’ adoption rate among farmers.

Key Considerations on Field Staff Qualifications

Corporate managers typically hire individuals with a strong technical background and/or proven trading skills. The reasoning is they will, on the one hand, be well equipped to train farmers to improve products’ yield and quality. On the other, they will be best poised to secure a sufficient of product at a good price.

As a result, investing more staffers’ soft skills is key towards implementing effective training and communications strategies to affect farmer behavior. They indeed allow staffers to identify impactful and inclusive trainings and other activities to boost farmer loyalty. These might include providing quality inputs, developing additional income-generating activities or circular economy opportunities…

These staffers are ultimately better embedded in their target communities. Farmers in fact relate to them more easily and tend to adopt their teachings.

Extending the Reach of Field Staff Thanks to Champion Farmers

In most cases, field staffers are unable or ill-equipped to interact genuinely and directly with all of the farmers engaged in any given supply chain. The number of skilled individuals (and the related costs) that would require would be simply too great.

Identifying Champion Farmers

Firms can however extend the reach of their field staff by identifying champion farmers to share training contents with 20 to 30 farmers. An effective network of champion farmers (also called volunteer leaders) can dramatically extend an training program’s reach and impact by multiplying paid field staffs’ effort by so many times. These champions effectively manage a version of customer service after field staff visits or training sessions. They maintain the link between communities and the firm.

Champion farmers are typically community members with leadership ability who volunteer to convey information from field staff to individual farmers. Effective champion farmers are typically articulate, dynamic community members who earn their peers’ respect and are willing to try new techniques. Well-organized farmer groups often name an individual to assume the role of a champion farmer.

It is therefore essential that champion farmers have the knowledge, resources and capacity to train farmers even in the absence of extension workers. This is key both to improve commercial linkages and farmers loyalty and to provide a technical follow-up that significantly improves good pratice adoption among farmers.

Best Practices for Champion Farmers to Boost the Effectiveness of Training and Communications Strategies

Best practices in increasing the effectiveness of champion farmers include:

- The inclusion of members of the farmer group in selecting their own champion farmers secures community support of the proposed program and farmers’ direct involvement in its ultimate success.

- Careful consideration of community dynamics is key in identifying the right profile for a champion farmer. For example, younger farmers tend to be energetic. Certain cultures, however, warrant naming older farmers for the respect and active listening they are traditionally endowed with.

- Written contracts between a given company, champion farmer and farmer groups helps clarify roles, responsibilities, and expectations before program launch. Businesses should consult local labor laws to clarify any potential obligations they may have to provide champion farmers, in terms notably of salaries and/or benefits.

- Off-site meetings and training sessions specific to champion farmers can reinforce training content and improve individuals’ facilitation skills. They also provide opportunities for champion farmers to share experiences and learn from one another.

- Detailed weekly schedules help the firm, farmer and farmer group track their champion farmer’s overall progress and achievements.

Incentivizing Champion Farmers

Champion farmers do not typically receive a salary. That said, the role requires a significant amount of time on their part. Businesses can motivate them and maintain their commitment over time through a combination of the following incentives:

- The provision of fertilizers and other inputs to create demonstration plots;

- Access to tools to facilitate training such as fuel for motorbikes as well as branded bicycles, hats, shirts, rain gear, backpacks, notebooks, and calculators supportive of group dynamics;

- Exclusive opportunities to learn new techniques;

- Opportunities to travel for meetings or visit other successful programs;

- Community recognition during meetings or via radio outlets;

- Opportunities to win prizes based on their group’s positive results.

Of these incentives, providing inputs is both the most expensive and most effective measure. The reason is quality inputs help champion farmers acheive higher yields. This has a tangible impact in that it demonstrates their effectiveness to other farmers.

That said, the incentives offered champion farmers should be enough to motivate them without negatively affecting other farmers.

Good Performance Depends on Effective Logistics and Strong Monitoring

Strategic scheduling, transportation and staff management increase the effectiveness of training and communications strategies. Below is a selection of best practices to that effect :

Locate field staff as close to farmers as possible

Field staff and supervisors may prefer to live in larger towns rather than villages. Living away from farming communities however increases commuting time and reduces working hours. Working in close proximity to farmers conversely increases trust and knowledge about farming practices and day-to-day issues.

Operating within a given community is always more effective than occasional field visits. Informal talks and group discussions help identify issues and possible solutions an external visitor will not necessarily be able to catch on to. Embedding staff at village level may require special provisions on a company’s part. These may include implementing tailored schedules (along the lines of four-day-on/three-day-offsite) and allowances to furnish or improve village housing.

Conventional Field Staffing Models

As a result, companies tend to follow one of two models (or a combination thereof):

- Field staffers are located at a central location like a crop-buying station or farmer training center. In the case of input firms, they can work from the offices of an agro-retailer and let farmers come to them.

- Field staffers work with farmers directly on their farms. This traditional extension model is more effective because it conveys a genuine effort to reach out and engage with farmers. This is also more expensive. Field staffers indeed have to travel to farmer communities… bearing in mind the previously mentionned constraints.

As a matter of fact, when field staffer work with farmers directly (or through a network of farmers) training sessions can take place in farmers’ own fields to address their specific concerns. This is especially useful for building trust and goodwill among farmers. It in turn reduces side-selling. Disputes between farmers and the firm are also resolved that much faster.

In other circumstances, a hybrid strategy makes more sense. For example, a farmer training center can house sedentary trainers for farmers to attend onsite sessions. It can also serve as a basecamp for mobile staffers. For input suppliers, having staffers work from the offices of an agro-retailer allows them to visit customers, identify issues and inform farmers on their products as they visit the shop.

Closely monitor the daily activities of field staff

Extension staffers work on their own most of the time. However, even with sound scheduling, field staff do not necessarily work in the location they are expected to on any given day. This could be due to constraints beyond their control, such as weather or road conditions. It could also be the result of poor work habits.

Given field staff recruitment is an inherently expensive proposition, companies must be able to verify the training is taking place as planned. It otherwise runs the risk its goals will not be met. Depending on their schedule supervisors can use unannounced visits to observe training sessions. That is likely the best way to monitor field staff performance and assess the effectiveness of extension contents.

Standalone GPS units mounted on motorbikes and vehicles and 3G phones are also useful tools to track field staffers on location. The cost of these technologies has significantly decreased and certain software packages can localize an entire extension workforce remotely. Most countries may choose among several remote vehicle monitoring system providers.

Generous mobility policy encouraging field, field and field activities

Implementing effective training and communications strategies also involves developing a clear policy to ensure smooth and effective field staff mobility.

For example, when field staffers are expected to visit workers in areas where public transportation is clearly insufficient, purchasing quality motorbikes is key, provided the company issues clear policies regimenting their use. Firms generally provide their field staffers with 125 CC off-road motorbikes so they may manage back roads between the units they expect to visit.

In such cases, it is also good policy to provide training for inexperienced riders to acquire the skills all staffers need to receive a motorbike license. A policy of gifting (or selling) motorbikes to field staffers at the end of their engagement life may encourage them to take better care of their vehicles. Policies that prohibit riding without a helmet, limit the number of riders on any given motorbike, restrict their use after working hours and establish procedures to notify the company of potential accidents help improve overall worker safety. The same goes for cars : their use should be carefully monitored, by appointing an individual to handle a log-book to centralize information on fuel consumption, milage and repairs.

It may appear anecdotal but transportation costs and investing in vehicles can account for more than 20% of an extension program’s budget in developing countries…

Clear Expense Policies Avoid Frustrations and Conflictual Situations

Develop clear expense policies for staff, workers and lead workers. Per diems, meals and transportation costs are potentially contentious. Effective training and communications strategies notably rely on clear policies that are communicated upfront, to avoid extended negotiations and perceived favoritism.

Mobile Technologies Reduce Costs and Increase Reach

Mobile technologies are a powerful tool for communicating with many people regardless of distance. Newspapers, pamphlets, instructional labels and inserts are examples of the printed media firms can use to communicate with workers. To be even more effective they can use these in combination with a growing variety of information and communication technologies.

Whereas mass media often enjoys a greater reach than conventional extension programs, the latter are more effective in terms of reinforcing learning and monitoring impact. Of late, ICTs have garnered much interest because they are less costly per worker than face-to-face communication. They can also reach a large number of workers and convey opportunities to lift learning reinforcement and impact assessment chokeholds. According to the IFC, systems that rely on ICTs usually cost less than $50 per worker annually. That said, the dearth and complexity of the information both collected and disseminated via ICTs remains limited. They should however be resolved as 3G networks expand.

Ksapa’s Take on Mobile Technologies to Back Training and Communications Towards Farmers

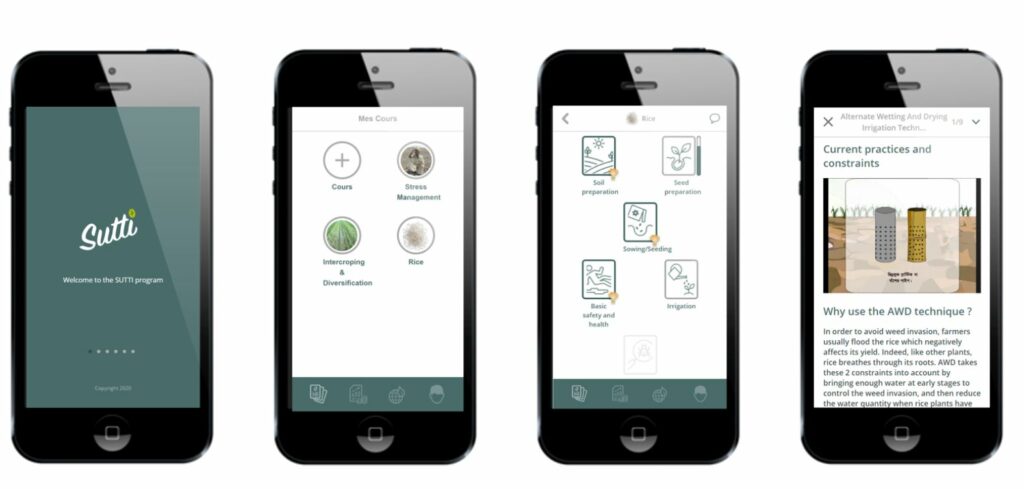

Based on this understanding, Ksapa developed its flagship SUTTI program to deliver scalable capacity-building programs across fragmented value chains. Our in-house digital suite indeed maximizes access to training via an e-learning tool and tracks program impact against social, environmental and economic performance targets. This ultimately helps industrial groups better understand their procurement map. It also powers information-sharing and data collection via a low-tech solution, making it altogether adaptable to most contexts and users, including vulnerable populations. In concrete terms, that approach allows Ksapa to reach out to 5 to 15 individuals indirectly for every farmer directly involved in a face-to-face session.

SUTTI is a large-scale impact program that leans on a hybrid capacity-building model. SUTTI indeed combines in-person and digital solutions to boost worker training and monitor impact in the process.

Conclusion: Selecting Effective Training and Communications Strategies

Designing an effective extension system involves balancing multiple competing factors that influence budget and farmers reach. The following list of questions and activities, though not exhaustive, provides a guide for determining the form and function of an effective scalable training changing smallholder behavior:

| Questions | Activities |

| Farmer density | How many workers need to be trained at each business unit or area? What is the distance between locations? How many worker meetings can an extension staffer organize per day? If workers are fairly dispersed they may only accommodate a single meeting per day. Conversely they may reasonably hold up to 4 meetings daily in higher-density areas. |

| Degree of aggregation | It is less expensive to train well-organized workers because some groups can share information among members without outside assistance. If workers are not aggregated, field staffers may need to form smaller groups before they hey launch technical trainings. |

| Farmer characteristics | Training must be tailored to farmers’ socioeconomic characteristics, including literacy levels and income. In addition, farm size and conditions (such as slope, age of tree crops and soil fertility) affect farmers’ ability to effectively use inputs and implement teachings. Firms should analyze an – if necessary – segment vulnerable worker populations to ensure their training experience is truly effective. |

| Presence of non-governmental organizations | The presence of local or international non-profits can be either an opportunity or a challenge. Costs may be reduced if the firm’s objectives can be supported by external organizations. However, the firm will likely have to match non-profits’ salary policies or risk their staff being poached. In either case, a close coordination between non-profits and firm is essential. A written memorandum of understanding may be useful to document their respective roles and responsibilities. |

| Past program review | It is critical for businesses to review past extension programs, development projects or governmental initiatives… Other organizations have implemented equivalent activities with similar impact and goals which offer strategic learning opportunities. |

| Farmers social profile | It is finally key to gauge field staffers’ capacity to understand the social challenges faced by farmers. Companies can then design impactful training programs accordingly. |