As part of the European Green Deal, an agreement was finally announced in December 2022 between the European Council and the EU Parliament on an anti-deforestation directive, aimed at eliminating the import or processing of products produced from deforestation. This agreement was highly anticipated, following the submission of a draft regulation by the Commission in October 2021 and the Parliament’s proposal for a revised, more ambitious version in September 2022.

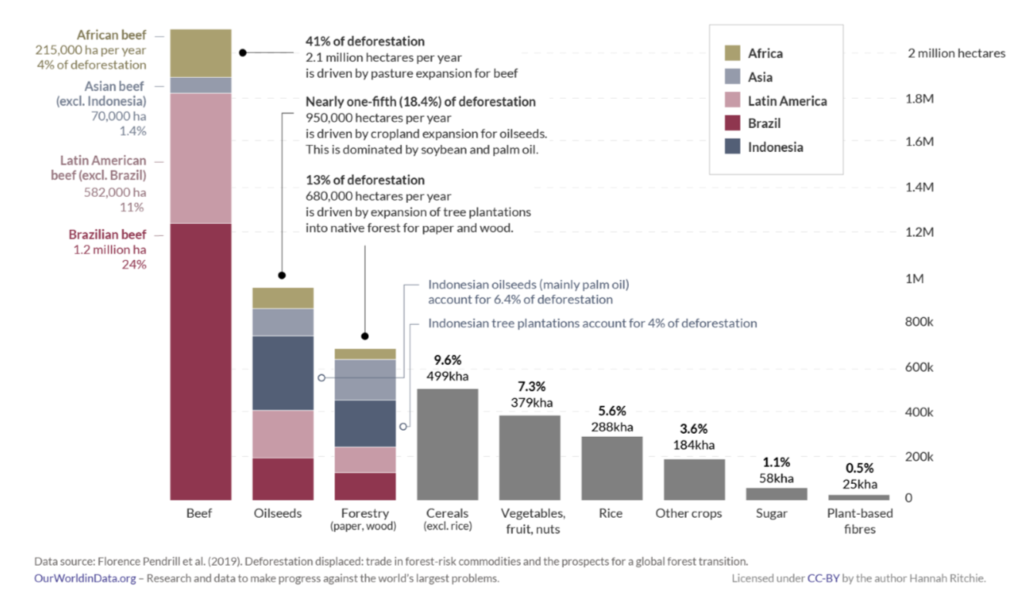

Although the final version of the regulation has not yet been published, and is expected to come into force in 2023, with effective application expected 18 months (for large companies) to 24 months (for SMEs) later, it is already time to get into gear, given the very significant impact on imports of the raw materials concerned: palm oil, beef, soy, coffee, cocoa, wood and rubber, as well as their derivatives. This list will be reviewed and, if necessary, extended periodically by the Commission.

Financial institutions are finally excluded from the scope of this list – but in reality, they remain indirectly subject to it, as they generally avoid financing non-compliant activities, and even less so if the financing is based on guarantees taken out on products at risk of being turned back or seized at the borders. On the other hand, many industrial companies and commodity traders will be faced with major changes in their sourcing patterns.

In practical terms, two main elements are expected to ensure compliance with anti-deforestation regulations:

- Traceability: to be able to import, sell or export products in the European Union, it will be necessary to provide, on a centralized interface to be developed by the European Commission, the list of the parcels on which the imported raw materials will have been produced, with the following information

- Description and type of product, including its commercial and scientific names

- Quantity in mass, volume or number of units

- Country of production

- GPS coordinates (Polygons) of all of the production plots

- Date or period of production

- Date of the transaction

- Name and contact information of a person involved in the production as well as the acquisition (including local buyers & intermediaries)

- Information on the absence of associated deforestation (since 2020)

- Information on compliance with the regulations of the country of production

- Due diligence: three levels of risk will be established according to countries and commodities, with reference to a list regularly updated by the Commission. Depending on the level of risk, due diligence in the supply chains will be required, with a robustness adapted to the level of risk. It is likely that a systematic cross-referencing of GPS data and analysis of proven deforestation risks, and a strict pre-selection of suppliers, will be necessary in the most at-risk areas.

The main problems lie in the implementation and social equity of such measures:

- This regulation will apply for example equally to the Brazilian beef and soy sectors, the main focus of deforestation and consisting mainly of farms of several hundred or even thousands of hectares, and to the natural rubber sector, where more than 85% of the world’s production is carried out on farms of less than 2 Ha. On the one hand, the registration of farm information (quantities, coordinates), in contexts where land tenure is neither secure nor definitive, is a real challenge, especially when we are talking about hundreds of thousands of small and vulnerable farmers, whose level of education is often very low. On the other hand, a number of the value chains targeted are articulated on several levels, several levels of intermediation from the initial producer to the industrial exporter. Consequently, the correspondence between administrative compliance and the reality of the physical flow of commodities will be difficult to verify, particularly at the first level of these agricultural chains: production at the farm level.

- These administrative constraints may very well place an additional operational burden on the shoulders of the most fragile players in these chains, who also do not have the means to invest in the technologies likely to collect the necessary information. The question of how to pay for this “compliance” effort is also highly problematic, as it will not be able to be borne by small farmers, but on the other hand, the dilution of responsibilities will make it difficult to implement (this is already the case in some certifications such as palm oil’s RSPO, which excludes small producers). In this context, one harmful effect, against which cooperation between States will not be sufficient, is the marginalization of small producers from sustainable and lucrative circuits, which are a priori more profitable and environmentally responsible. This would result in the creation of two-speed agricultural production markets, one that complies with European requirements or sustainable markets, the other that will be “for the rest of the world” without any impact on the reduction of deforestation and putting small producers at social, economic and environmental risk.

- They also raise questions about data privacy, if only to be consistent with the European RGPD regulation: the distinction between private activities and the family sphere is not obvious and the provision of “Business Details” of each of the farms concerned will require structural safeguards to avoid the recovery and reuse of the data thus collected, which will necessarily include a personal dimension, both for economic or political purposes.

Therefore, in light of the progress that will be made with the emergence of anti-deforestation regulations, it appears key to the equitable implementation of these regulations to design and implement mechanisms that allow for the inclusion of small-scale farmers and the change of practices to their benefit.

To bring such populations on board on a large scale, programs must be designed to provide multiple benefits beyond strict compliance. The requirement to ensure transparency at all levels of supply chains is also an opportunity to integrate them into a more ambitious approach.

How does SUTTI, Ksapa’s solution, respond to the new import constraints in the EU?

Ksapa, a mission-driven company, has developed the SUTTI initiative, whose objective is to include small producers in the value chains of large industrial groups through training and the adoption of practices that generate social, economic and environmental impacts throughout the production chain.

In this respect, Ksapa has developed for 3 years and implemented in the field, within its SUTTI initiative, its own low tech application suite, coupling content dissemination and data collection, in order to have a significant geographical impact responding to current issues. This application, in addition to training vulnerable small farmers (in-person training supplemented by an adapted e-learning application), collects a whole series of data necessary for the proper accompaniment of the farmers, making it possible to assess first the adoption of practices, then the impacts that these trainings cause on the life of the farmers (income, diversification, resilience, working conditions…), and to follow their sales transactions.

Thus, SUTTI makes it possible to

- Know and understand the farmers, their constraints, their way of producing, the quality and quantity of what they sell and where they sell it.

- Assess the impact of the adoption of new agricultural practices on the standard of living and resilience of farmers, and identify the origin of products from the first stage of the value chain, the most fragmented level

It is therefore the issue of traceability that is covered with the primary intention of training farmers.

In addition, at each stage of the implementation of the project from its design to its operational monitoring, data will be collected in compliance with the EU RGPD policy:

- At the time of recruitment, the farmer will provide data mostly on his farm, including GPS coordinates allowing cross-referencing with deforestation risks, and partly on personal profile (accessible only to authorized local field officers)

- At the time of training, the farmer will describe his or her farming habits (nature of inputs, costs and profits)

- Each month, his performance (volume harvested and sold, production costs, quantity and quality of inputs, …) will be monitored through the adoption of new practices.

- At the time of sale, producers and sellers will jointly confirm the quantities purchased and indicate the corresponding price.

- Finally, the aggregation of all these data will provide a dynamic and real-time view of supply basins for different types of commodities.

However, it is easy to collect data without verifying their “reality on the ground”, which is why the SUTTI initiative involves all project stakeholders from the outset of the project in order to establish an unbiased inventory of the sector, facilitating the selection of common objectives. This equal level of information and understanding allows for the establishment of trust between the partners of the project coalition. The latter, which is essential between producers and buyers, improves the quality of information collection, which then reflects “a little better” the reality on the ground, since its sole purpose is to report on impacts that are known and shared by all. However, the quality and regularity of data collection will be key for the proper respect of regulations, in the analysis and assessment of risks as well as in the conformity of the monitoring of transactions within the parcels concerned. These parcels are be subject to a recording of GPS coordinates forming polygons in order to cross-reference with the risks of deforestation.

Moreover, at the time of the transaction, the data is double-checked thanks to the joint validation of the buyer and seller. Indeed, even if the technical training is complemented by administrative and financial training (how to calculate a yield, a profit or a quantity of fertilizer), these verifications appear to be necessary because of the different levels of understanding of a single question.

Although this collection system appears to be an additional burden for farmers, it is part of a long-term approach that will allow them to better understand and monitor their daily work, to share their doubts with experts and, ultimately, to increase revenues, access to markets and make savings. It will in particular allow access to markets that have closed their access to raw materials related to deforestation.

The benefits for farmers therefore far outweigh the time spent providing this data. In an impact study conducted in September 2022 on one of our SUTTI programs in Indonesia, for example, more than 90% of the farmers surveyed claimed to have seen an increase in the yield (on average 12%) thanks to the adoption of the new farming practices2 recommended (natural rubber sector in Indonesia, study of 244 farmers in the Jambi region) a few months after the start of this multi-year program, with multiple positive externalities such as more gender or youth inclusion and lesser accidents at work enabling a program-related satisfaction rate of more than 82% within farmers.

For a competitive cost per farmer, manufacturers and importers have a turnkey solution that facilitates the comparison of reliable field data with satellite imagery, thus complying with new EU requirements, while generating a significant positive impact on the lives of major food and agricultural producers.