The subject of climate, sustainability, or environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosures has gained a lot of traction and attracted a lot of interest from investors, corporates, and regulators in the past few years. Indeed, it is now widely accepted among investors and corporates that climate change does have an impact on a company’s operations and so on its financial value, and thus, should be seriously considered.

However, it appears that shareholder activism is still required to get some corporates to provide adequate disclosures on ESG issues or to make the necessary changes. One can think of Engine No. 1 and its campaign against ExxonMobil, or BlackRock’s increasing activism in Berkshire Hathaway for example. Indeed, while voluntary disclosure, through reports or websites, is common practice in most large corporates in the U.S., not all companies disclose this information, and when they do, there is a lack of comparability across these climate disclosures; thus, stressing the need for a common framework.

With increasing interest & pressure in the U.S. and with Europe having taken the lead on the matter, Joe Biden’s administration began to lay out plans for a renewal of climate disclosures in September 2021 Executive Order in an effort to catch up with the European bloc.

In this blog, we will compare the SEC and ESMA’s leadership positions on ESG disclosures and provide a brief overview of the main divergences. We encourage you to read our Briefing Paper to get additional insights on the topic.

Climate Disclosures Race, SEC vs ESMA: To Lead or Not to Lead

1. SEC: WAIT AND SEE

Until recently, the SEC did not have any plans to mandate line-item ESG disclosures. In Management’s Discussion & Analysis (MD&A) amendments and concurrent statements, the SEC explicitly acknowledges the absence of new climate disclosures. Indeed, while climate disclosures are complex, difficult to verify, and uncertain – involving estimates & assumptions – most at the SEC want to stick to the materiality principle of the SEC which only focuses on financial materiality (if a piece of information is financially material to an investor).

However, with the new administration coming in, ESG disclosures became top priority. In early 2021, the SEC Division of Examinations identified ESG as a top review priority for investment advisers. The SEC Division of Enforcement created the “Climate and ESG task force” to analyze “disclosure and compliance issues relating to investment advisers’ and 1940 Act funds’ ESG strategies”. Additionally, after a period of public consultation demanding inputs from market participants, the ESG subcommittee of the Asset Management Advisory Committee (AMAC), chaired by Edward Bernard (Senior Advisor to T. Rowe Price), outlined 5 recommendations on issuer and product ESG disclosures. In brief, these recommendations urged the SEC to determine a framework to report ESG matters, notably by looking at third-party frameworks, such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Additionally, the Committee stated that it may be premature for the SEC to broadly implement mandated ESG disclosure through specific regulation. Instead, the Committee recommends revisiting the issue of a more codified framework once consistent and comparable ESG metrics achieve widespread market adoption.

However, the apparent “wait and see” approach of the SEC, also justified by increasingly divergent opinions amongst its commissioners – as “consistent, comparable, and reliable” ESG information is not understood in the same way by everyone – came to a stop in March 2022 with the publication of its proposal for mandatory climate disclosures, largely supported by Chair Gary Gensler. Indeed, as Chair Gensler stated in his supporting statement, through this proposal, the SEC is responding to investor demand for meaningful, consistent, reliable & comparable information on the relationship between climate-related risks and companies’ financial performance.

2. EUROPEAN SECURITIES & MARKETS AUTHORITY (ESMA): SHOW LEADERSHIP

So far, the EU has led ESG regulation among world capital markets through climate policies, green bond issuance, and renewable energy integration.

Indeed, through the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Taxonomy Regulation, the EU was the first economic union to mandate climate disclosures for corporates. Its CSRD applies to no less than 55,000 European companies. In addition, as all major corporations with subsidiaries in the EU are forced to comply with its regulation, ESMA’s reporting directives are thus paving the way for a global framework. It is in fact ESMA’s goal, as stated by ESMA’s Chair, Steven Maijoor, in its 2020 European Financial Forum speech to consolidate the existing numerous ESG frameworks and standards and for Europe to “show leadership in this area” by playing an important role in promoting this consolidation at the international level.

Policies defined and put in place at the European level (CSRD, SFDR, Taxonomy Regulation) have driven legislative initiatives in member states of the EU, and the UK, to define robust ESG disclosure regulations at the country level in line with European level directives. Such examples include France’s Article 173-VI of Law on Energy Transition for Green Growth, the UK Financial Conduct Authority’s climate change and green finance proposals, and the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority’s guidance notice on dealing with sustainability risks.

ESG Reporting: Divergences between SEC & ESMA

While both regulators have the same goal – providing consistent, reliable, and comparable information to investors and market participants – their scope, understanding, and approaches differ.

1. SCOPE OF DISCLOSURE REGULATIONS & UNDERSTANDING OF ESG DIMENSIONS

Indeed, the scope of the EU & US regulations differs. The CSRD regulation applies to a lot more companies than the SEC proposal: around 50,000 in the EU compared to only listed companies in the US.

Moreover, the SEC’s proposed rules solely focus on corporates. In fact, issuers and asset managers are not yet concerned by these developments. On the contrary, the EU has developed specific frameworks, namely the SFRD & Taxonomy Regulation, for issuers & financial institutions; although a follow-up proposal from the SEC tailored to financial institutions is likely to be drafted.

Additionally, the understanding of what constitutes the 3 dimensions of ESG differs from across the Atlantic. In particular, the “social” and “governance” dimensions and how they are understood differs greatly, as the underlying social concepts are not the same. Indeed, while the EU has a deeper understanding of the social dimension, due to its history of social conflicts, debate, and legislation around decent work notably, the US is much more advanced when it comes to governance aspects, as it is traditionally associated with the American conception of business administration. Among the 3 dimensions, the environmental component is understood more similarly by both the regions. The underlying environmental issues and risks are indeed fairly uniform between both regions: both the United States and Europe have witnessed cataclysmic weather patterns over the past years.

2. DISCLOSURES & MATERIALITY: DOUBLE VERSUS FINANCIAL

Besides the differences highlighted above, the SEC and ESMA’s approaches mostly differ in their interpretation and enforcement of the materiality principle.

The accounting principle of materiality of financial information states that corporate information should be disclosed if “a reasonable person” could consider it important for their decision-making process. This is what makes that information ‘material’ to the investor.

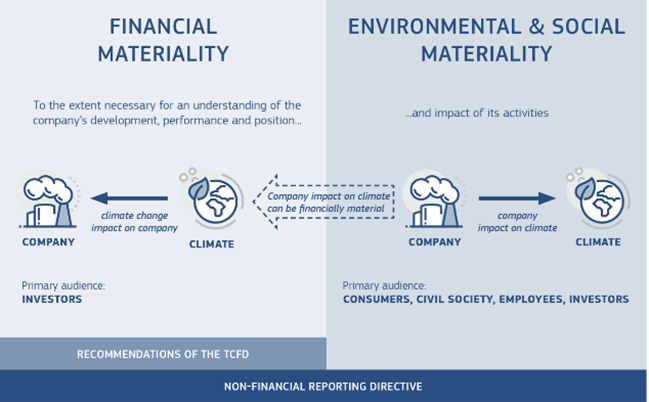

On the EU side, the CSRD and SFDR regulations push forward the notion of double materiality.

Thanks to the work of the TCFD, the notion that climate-related impacts are material for a company is now widely recognized. Indeed, they directly impact a company’s value (financial materiality, or “outside-in” perspective). Meanwhile the impact a company may have on climate, planet, or people (environmental and social materiality, “inside-out” perspective), should also be considered material.

That’s at least where the E.U. stands, as conveyed by its description of double materiality illustrated below.

On the contrary, the definition of materiality used by the SEC is rooted in the opinion articulated by Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall in the case TSC Industries v. Northway, describing “an item of information as material if there is any substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider the information important in deciding how to vote or make an investment decision”.

In this respect, the role of the SEC is defined as assessing any new potential disclosure rule against the issue of whether or not an investor would consider it to be financially material. That is to say, material in terms of corporate value.

As such, the SEC sticks to the SASB definition of materiality, for which a material piece of information is one “expected to influence an investment decision that users make on the basis of their assessment of future enterprise value”.

To summarize, while the scope of regulations, underlying metrics and estimates can be completed or amended, a common ground of understanding is necessary for comparability. And that is what we lack today between the SEC’s and ESMA’s approaches.

Conclusion

Therefore, while the EU’s and US’s respective rules provide some common ground (based on TCFD & other international frameworks), important differences remain; most notably, the diverging views on the concept of materiality, which is yet to be resolved.

This can pose problems in the future, particularly in terms of comparability across regions and companies, as materiality is the basis for responsibility. Indeed, the concept of materiality inherently poses the question of responsibility and how to measure up to one’s responsibilities (with respect to the environment, the people…). If this concept is not understood in the same way across the Atlantic, then it leaves room for interpretation and thus lack of action.

Meanwhile, various sustainable finance taxonomy efforts are developing worldwide. In late 2020, for instance, the EU and China launched a working group hosted by the International Platform on Sustainable Finance to develop a “common ground taxonomy”. Other markets, including the ASEAN region, Canada, China, and Japan are following similar stages of consultation and evaluation to develop their own approaches.

Adrien is a SUTTI Program Officer. He’s responsible for the development, operational implementation, and monitoring of SUTTI programs. He participates in designing financial structuring schemes leveraging SUTTI’s impacts.

He has previous experiences in various industries, within public, private, and non-profit organizations. Before joining, he was involved in microfinance and social entrepreneurship initiatives in Cambodia and the Philippines, after working for Danone and RATP.

He holds a Master’s in Finance from Paris-Dauphine University, as well as a Master in Management from ESSEC Business School.

He speaks French, English, and Spanish.