The climate transition necessarily requires a priority treatment of the issue of so-called « leaky homes ». Ksapa examines the corresponding stakes and outlines a solution. For France alone, improving the energy performance of these assets may, after all, generate 113 billion euros within the next decade…

The European Commission set the course for the climate transition. Its 2030 target reduction of greenhouse gases’ emissions now sits squarely at 55%. At least. Companies are increasingly joining movements such as the Science-Based Targets initiative or the Race to Zero. Central banks are coming together under the banner of the Network for Greening the Financial System. Investors are organizing to help their portfolios evolve, through initiatives such as the UNEP-FI’s Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance.

While certainly beneficial, there is more to the energy transition than commitments and targets. It cannot be solely about transitioning assets and activities that are already exemplary with regards to climate. According to the UN-PRI, 30% of GHG emissions come from the real-estate and construction sector.

Boosting Europe’s renovation rate to an annual 3% (versus 1% at present) and sustaining that level until 2050 could in fact reduce energy demand in buildings by up to 80% by 2050. This would in turn dramatically reduce related GHG related emissions. Bringing all buildings up to current efficiency standards would require investment of €1 billion a day, every day, until 2050. Such measures also carry potentially substantial benefits in terms of energy savings and GHG emissions. Encouragingly, owners of green buildings report a 7% “green value” boost in asset value over other buildings.

The Urgent Need to Address « leaky homes »

In that respect, the climate transition inevitably involves addressing so-called « leaky homes ». We have known about the urgency of tackling this sensitive matter for years, yet implementation remains a bottleneck.

That said, « leaky homes » represent approximately 40% of households in Bulgaria. That in part explains why the winter mortality is surprisingly higher in the South than in the North. In Europe, the poorest of households are 4 to 5 times more exposed to living in « leaky homes » than their more affluent counterparts. In fact, 30% of low-income households are unable to keep their homes warm…

There are of course obvious discrepancies from one country to another. For example, a British home loses heat up to three times faster than its Swedish counterpart. Meanwhile, the proportion of people living in « leaky homes » in the UK is almost a third higher than in France.

The French Government’s approach to tackling Leaky Homes

The French government commissioned a report on « leaky homes » in March 2021. A key component of the new Climate and Resilience law, the report outlines various measures to accelerate and dramatically bolster the renovation of low-performance buildings. It goes on to recommend the following:

- The creation of a special status of “global partner” to carry out diagnoses and issue renovation proposals to relevant households;

- The granting of public aid based on combined criteria of income and energy ambition;

- The reactivation of the “transfer advance loan” to encourage the renovation of housing occupied by people over 60.

On a different front, large businesses are multiplying commitments to carbon neutrality. This, over a more or less long period of time. This is great news, provided these commitments are implemented, as soon as possible. That said, tertiary or industrial buildings that could qualify for the « leaky building » terminology remain a blind spot.

Turning back to the issue of housing, « leaky homes » obviously present a double environmental and social impact.

The Socio-Environmental Impact of « leaky homes »

On the one hand, « leaky homes » are most exposed to a rise in the price of carbon. The latter recently briefly rose above €40 per ton of carbon equivalent. This was a major departure from years of stagnation below the €10 threshold on the regulated European market. This would substantially hike the cost of energy for corresponding households and eventually shave the value of these real-estate assets.

On the other hand, the poorest of populations typically own or live in « leaky homes ». Some even face severe difficulty. In France, 37% of these « leaky homes » are occupied by households living under the poverty line, for example. Given the post-Covid economic crisis, their investment capacities are mechanically limited.

The Yellow Vest movement was initially born out of protesting a new carbon tax. It certainly reminded decision-makers energy insecurity and economic difficulties go hand in hand. As a result, there can be no real energy transition without taking into account the social underpinnings of « leaky homes ». That and the equity necessary to truly address these disparities.

How then should the renovation of these « leaky homes » be organized or promoted ? How do we collectively insure we fully take in to account the lack of private means allocated to the matter?

Concrete Financing Solutions

A (small) part of the answer may lie in France’s new Climate and Resilience Bill. It notably proposed a ban on renting out non-energy efficient housing by 2028. While discouraging for indelicate owners, it is far from ambitious enough – and, in any case, too late.

On top of above-mentioned solutions, we recommend a solution adapted to the current monetary context, characterized by negative interest rates and abundant liquidities. This indeed constitutes a unique opportunity to organize an incentive system for an accelerated renovation of « leaky homes ». This way, we collectively stand to deal with this strategic issue at a ultimately affordable cost. We could even create permanent jobs in the process!

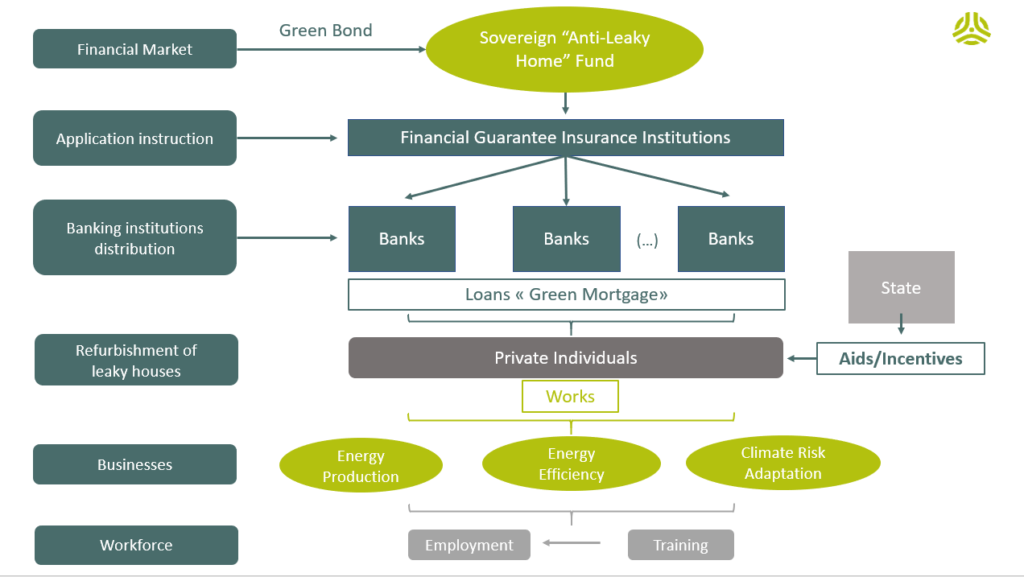

As it is, the renovation of « leaky homes » (i.e. with poor Energy Performance Certificates) is, in many countries, subject to diverse advances and subsidies. On top of that, we suggest banking institutions offer a specific Zero Rate Loan – or, at the very least, a reduced interest rate. This could be fed and guaranteed by a fund under State supervision. It would certainly help households to make the necessary investment, while bridging any gap left by subsidies.

Granting Preferential Loans to Ease the Renovation of « leaky homes »

- The purpose of these loans is also to cover construction work or equipment related to improving energy efficiency and/or installing clean energy production devices for self-consumption. The same loans should also be extended to renovation work related to climate risk adaptation in certain areas, not just limiting a household’s GHG emissions. This may prove instrumental in hedging the financial impact of extreme weather events or chronic risks due to these disruptions. Both for public authorities and for communities.

- These loans would not command any reimbursement before asset sale. They would in fact be open to all private owners of « leaky homes ».

- A new guarantee instrument could be created to offer a reduced mortgage registration rate. This should be made possible though the digitization of national mortgage registers. This “green mortgage” would aptly complement conventional guarantees, such as first or second rank mortgages.

- The risk carried by these loans would be controlled insofar as the energy renovation reinforces asset value. It would also erase any drop in value on poor energy efficient assets, by valuing their energy performance. That gap will incidentally become increasingly significant.

- The state would set up an ad hoc fund with a measured risk of default. This can be financed by the issuance of a green bond, which the state’s backing would render particularly attractive. In fact, 10-year bonds enjoyed a negative rate as of March 2021 in many major countries. The sustainable bonds market is expected to reach 600 billion euros in 2021. This is supported by European regulatory developments, including the upcoming green taxonomy and green bond standards. The resulting fund could ultimately be operated by State players or Financial Guarantee Insurance Institutions (to support distribution by banking institutions).

Relevant Solutions in the Context of an Inclusive Recovery

- The proposed scheme’s implications in terms of jobs would be significant. This is consistent with many national ambitions to train and develop the professions of the future – and particularly those linked to the ecological transition – as part of their recovery packages. It also promises qualification and “local by nature” opportunities for those affected by the Covid-19 crisis. That way, relevant training courses could secure environmentally-friendly State recognition (and attached incentives, in all likelihood).

- Addressing « leaky homes » through our proposed scheme hinges on a large-scale training plan. It should focus on 3 pillars of energy transition diagnoses and advisory, but also equipment installation and renovation work – and finally, equipment maintenance so essential to sustain these improvements in the long run.

Conclusion | Operationalizing a Fair and Sustainable Transition

The proposed scheme stands to promote and operationalize a fair energy transition. It advantageously limits the exposure of the most modest households to the consequences and risks of climate disruption – whether physical or transitional. Finally, this solution promises to generate qualified jobs firmly anchored in local communities.

20+ years of experience in investment & asset management.

Raphael Hara works on relationships between finance and sustainability, in particular through the development and management of impact investment funds and projects.