COP 28 will have produced some results. A certain momentum on the loss and damage fund, the tripling of renewable energies, efforts focused on energy efficiency and a spotlight on methane. Controversially, the inclusion of targets for fossil fuels more than 30 years after the first COP resulted in a historic breakthrough with a call – hailed by some albeit differentiated – for organizing a transition away from fossil fuels. This in order to reach carbon neutrality in energy systems in 2050. The fears expressed by others – including us – are mainly due to the inability of governments in the past to meet the commitments and targets set in previous COP agreements.

But the COP format now mainly produces frustrations. It struggles to find topics enabling to synchronize the political, social, and environmental agendas of participants coming with very different contexts and imperatives.

Another notable element in this COP 28, was the policy of distancing and limiting civil society actors from their historical role. It generated legitimate frustrations and misunderstandings, given their contribution to awareness of climate issues and to driving progress in decision-making in the last 3 decades.

Maybe it’s a sign? In the corridors of COP28, the suspense around the final text was strangely absent from the discussions in which we participated with our contacts among the approximately 80 to 100 thousand participants in this COP. Projects and solutions: this is what was occupying people’s minds, more than the follow-up of new commitments. Certainly, those are symbolically and politically significant. But they generally remain inoperative & insufficiently efficient.

Ksapa aims to find pragmatic ways of making concrete progress on these issues.

Agriculture is a subject that has historically received little attention at the COPs. It is regrettable … but the subject is finally starting to gain more traction. We therefore contributed to various discussions in Dubai to discuss how to feed the greatest number of people, create and maintain employment in rural areas attractive to those with limited education, while decarbonizing agri-systems. Agriculture is both part of the problem and part of the solution. Particularly in the 500 million small family farms on which at least a third of humanity directly depends, it combines crucial environmental, social and economic issues. Here’s an overview.

1. Role of Agriculture in Climate Change

The role of agriculture in climate change has evolved gradually. The stalled discussions on whether or not to exit fossil fuels, and when, prevent us from exploring pragmatic and effective levers for phasing out fossil fuels. We need to feed the population and many inputs use fossil fuels. Although the latter provides part of agricultural yields, they are increasingly expensive, are sometimes unavailable, pollute water and weaken biodiversity. They also pose health challenges for users who are generally poorly informed and equipped. Transforming food production, processing and consumption for the good of the environment and human health is now an obvious fact that is being implemented very gradually at every COP.

Although the need for change is now widely recognized, there is also a growing awareness of the potential threats to farmers’ livelihoods: they are generally old and poor. The question is therefore no longer whether we should get away from fossil fuels. But rather how to do it, by supporting farmers to learn about alternatives, and in their ability to make a decent living income from these rural activities. Solutions exist – such as the production of organic inputs on the farm -: they provide long-lasting economic, environmental and social benefits. But they require gradual introduction, sustained support and training. The example of Sri Lanka, where a purely political decision largely linked to the lack of foreign currencies to allow imports, was suddenly implemented, even though the actors of civil society as well as certain public organizations had the approaches and methodologies to organize this change gradually. Without time, without means to deploy these supports, farmers were unable to adapt their activities and work without inputs without significantly reducing their productivity.

The concept of “just transition” to be applied to agriculture to ensure decarbonization is therefore essential. This transition aims to minimize negative impacts on workers as the agricultural sector makes the necessary changes to reduce its climate footprint. The “just transition” approach focuses on supporting farmers through these changes, particularly those already experiencing difficulties, and addressing deep injustices within the food and agricultural system.

Finally, even if governments applied their current carbon commitments, we would still be on a trajectory of 2.7 degrees. Maintaining the 1.5° objective desired by many delegations remains wishful thinking at this stage. Caution requires us to prepare and plan for the consequences of a trajectory around 4 degrees, given the lack of implementation of the plans and mobilization of funds announced since 2015 and COP 21. The expected effects are catastrophic. An IPCC report has already demonstrated in 2018 the magnitude of impacts to be expected based on a gap of 0.5 degrees, between a trajectory of 1.5 and 2 degrees. As a result, while agriculture is undeniably responsible for a significant share of global emissions, it is also vulnerable to the effects of climate change such as droughts, floods and wildfires. And it is particularly so at the level of small family farms that have neither the resources nor the knowledge to engage in this adaptation. Beyond extreme weather events, chronic changes in temperature and precipitation patterns pose challenges to crop yields, requiring a comprehensive approach that considers both mitigation and adaptation to climate change.

2. Ksapa and its activities to promote low carbon agriculture

Ksapa contributed to various exchanges, notably as guest speaker organized by the International Labor Office on the issues of circularity within SMEs, and by the Sri Lankan delegation on the question of the inclusiveness of voluntary carbon markets. Different stakeholders with similar issues across countries in the Global South, regarding the success of large-scale implementations of agroecology, were highlighting the importance of lessons to be learned from different crises and of technical, digital efforts and funding to be organized with farmers for successful transitions. The sharing of ideas and good practices between farmers is particularly crucial, favouring a bottom-up rather than top-down approach. Other territorial stakeholders, such as authorities or buyers, must therefore play a role in regulating and equipping these rural communities while leaving room for empowerment. At the heart of this, digital solutions like SUTTI Digital Suite make it possible to disseminate knowledge, facilitate peer-to-peer sharing and collect data by applying pragmatic data science approaches to monitor and manage the deployment of programs in rural areas – even with poorly connected beneficiaries.

Our highly promising discussions with global Tech for Good players as well as with cutting-edge West African research institutes were focused on the combination of our low- tech solutions serving rural communities and our data collection and distribution approaches, and analysis with cutting-edge technologies using satellite networks and artificial intelligence. For example, these players can estimate the impact of the adoption of regenerative agriculture practices on carbon sequestration in the soil or predicting a few weeks or even a few months before the production volumes by jurisdiction or even by plot. How can personalized information be sent to farmers in spite of basic, outdated equipment and limited connectivity? How can we combine analyzes “from the sky” with field feedback to improve the relevance of information processing? This is one of the challenges that we want to tackle in our programs in South and Southeast Asia, and in West Africa and for which partnerships are an essential lever.

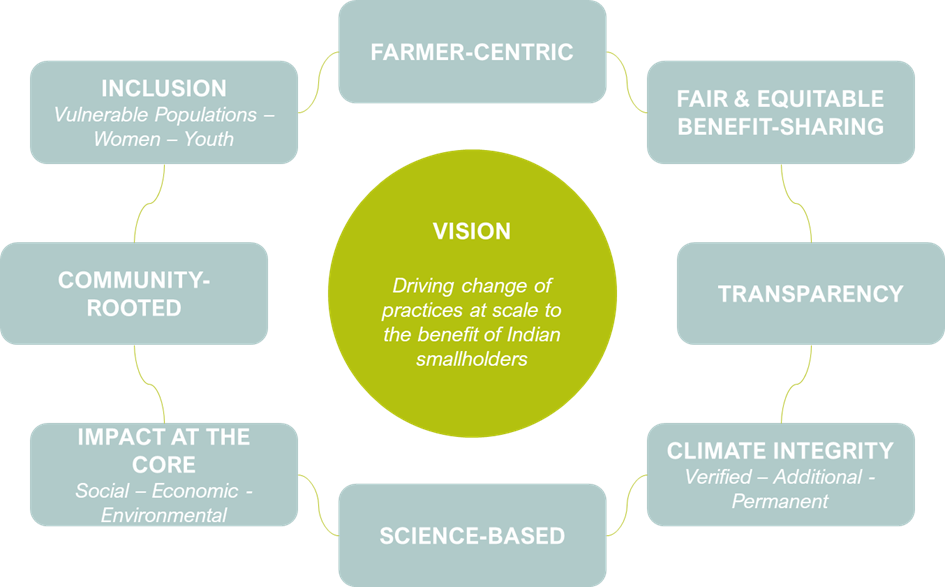

3. Principles to take into account to succeed in the just transition of agricultural activities towards de-carbonized models

Four key principles must be taken into account to guide a just transition in agriculture:

- Addressing inequalities in programs: Rural areas are often less developed than urban areas: roads, internet access, or access to education. These are dimensions of inequality to be taken into account in the design of programs which must compensate for all or part of these inequities. The success of programs supporting farmers in rural areas in decarbonization trajectories must rely on hybrid systems in which a human presence facilitates access and adoption of knowledge while being supported by digital tools designed to operate in these environments. This hybrid logic is essential for planning programs on a scale while compensating for several territorial inadequacies such as difficult mobility due to a lack of quality roads, the low level of education of beneficiaries or the low digitalization of their activities.

- Transforming the food system for people and climate: Food systems are sometimes mainly oriented towards monoculture and export. While these activities generate income, they are exposed to fluctuations in market prices and diseases that can wipe out the entire crop. Furthermore, they must also be put into perspective of increasingly significant food security and subsistence issues. Many decarbonization schemes on which we work combine these activities with diversification activities on the same plots and by complementing monocultures with different species. Hence, ensuring both a significant increase in biomass-carrying carbon sequestration while offering income relays (spices, cash crops, etc.) and food resilience (legumes, flour for animals, etc.).

- Ensuring inclusiveness in planning processes: The participation of marginalized groups, such as women, migrants, youth and smallholders, from the start of the transition process, is essential to be able to achieve a just transition. Beyond institutions and stakeholders generally well identified in the territories, it is by contacting marginalized groups directly that we can ensure the dissemination and implementation by these key players who make farms run, thus ensuring the future of agricultural activity. It is not just an ethical question of justice and equity, but also of program effectiveness. 85% of agricultural activities in Malaysia are now carried out by migrant workers, for example. If the cocoa sector in Côte d’Ivoire is one of the few in the world not to be unbalanced by the ageing of farmers – although other factors might weaken it-, it is because migrant workers are ready to work in these value chains, which do not ensure a decent income but do enable escape extreme poverty.

- Develop a comprehensive framework that takes into account diverse perspectives: Carbon is a technical subject that does not interest the rural agricultural world in general. They are, above all, interested in the capacity of their farm to help them earn a decent living income, ensuring that they can meet daily costs. Agronomy and associated techniques can be complex and require technical background, out of direct reach for farmers who often stopped their school studies at 12 or 15 years old. It is essential to design programs that take into account the point of view of beneficiaries to prioritize and organize a decarbonization trajectory & roadmap that can embark & motivate them. However, if voluntary carbon markets are to develop as they are supposed to without being caught up in controversies over green, social, or SDG washing, making them more inclusive is inevitable. No transition will be possible if it is not fair, and the credibility and legitimacy of these markets will not only rest on their rather technical “carbon credit integrity” but also on the social impact carbon credits can bring. Furthermore, the demand for “AFoLu” (agriculture, forestry and land use) credits is expected to far exceed the land available for reforestation and afforestation over the next two decades. It is therefore essential to use carbon markets to develop inclusive carbon projects for smallholders, transforming existing farms and helping them transition to regenerative agriculture. Finally, the benefits for farmers must outweigh – by far – the direct additional income they can earn from the carbon credit sales to be both equitable and successful. Increasing yields, reducing chemical inputs, diversifying income, valorizing by-products, etc. must be the main benefits (rather than a share of the sale of carbon credits, which is necessary but probably insufficient) of the change in practices undertaken.

Conclusions

The challenges of agricultural transitions are numerous, notably the resistance of farmers, cultural links with food, the complexity of finding solutions beneficial to all – or sometimes reluctance to change from certain stakeholders having interest in maintaining the status quo. The seasonal and transient nature of agricultural work presents an additional obstacle. Finally, agricultural workers are often poorly represented in unions, making mechanisms to take their interests into account more difficult.

There is an urgent need to transform agriculture to mitigate its contribution to climate change and adapt to it. This cannot go without highlighting the importance of a fair transition – and of taking the perspective of small farmers to integrate social justice, inclusiveness and support for the most vulnerable people affected by these changes at the very core of agricultural transition programs.

20+ years of experience in investment & asset management.

Raphael Hara works on relationships between finance and sustainability, in particular through the development and management of impact investment funds and projects.

-

Raphael Hara

-

Raphael Hara

Président et Cofondateur. Auteur de différents ouvrages sur les questions de RSE et développement durable. Expert international reconnu, Farid Baddache travaille à l’intégration des questions de droits de l’Homme et de climat comme leviers de résilience et de compétitivité des entreprises. Restez connectés avec Farid Baddache sur Twitter @Fbaddache.

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid BaddacheSeptember 29, 2023

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache

-

Farid Baddache